The invasive New Zealand flatworm is entrenched in the north of the country, and slithering south.

Gaby Bartai talks to the research team who are on its track

By the time you find your first New Zealand flatworm, it’s too late. Lurking under stones, planks or pots, they keep a low profile, but they are impossible to eradicate and their effect on soil ecology is profound. New Zealand flatworms feed exclusively on earthworms, with such efficiency that populations can be virtually wiped out. This has serious repercussions for soil structure and fertility.

Enjoy more Kitchen Garden reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

I first encountered flatworms some 15 years ago, in my father’s Shetland garden. Enriched with barrowloads of compost, it should have been teeming with earthworms. By the end of his time there, hardly any earthworms were left. Flatworms – thought to have arrived with topsoil for a local building project – were squashed on sight, but it was a losing battle.

Today, my father gardens in central Scotland, and as we work the soil there, uncovering fat pink earthworms in every spadeful is a delight. This time he is taking no chances: any plants he is given are quarantined and repotted, no soil or compost gets moved in, and the boots I wear there stay there.

The good news is that forewarned, you can keep flatworms out. Most Scottish gardeners know to be vigilant, but gardeners in England tend to be less well informed, or to assume that it’s a Scottish problem. No longer: the infestation is spreading south, and gardens are especially at risk. Flatworms like cool, damp conditions, so gardens and allotments, with well-watered soil, plenty of earthworms and lots of refuges to hide under, make attractive habitat.

Tracking the flatworm

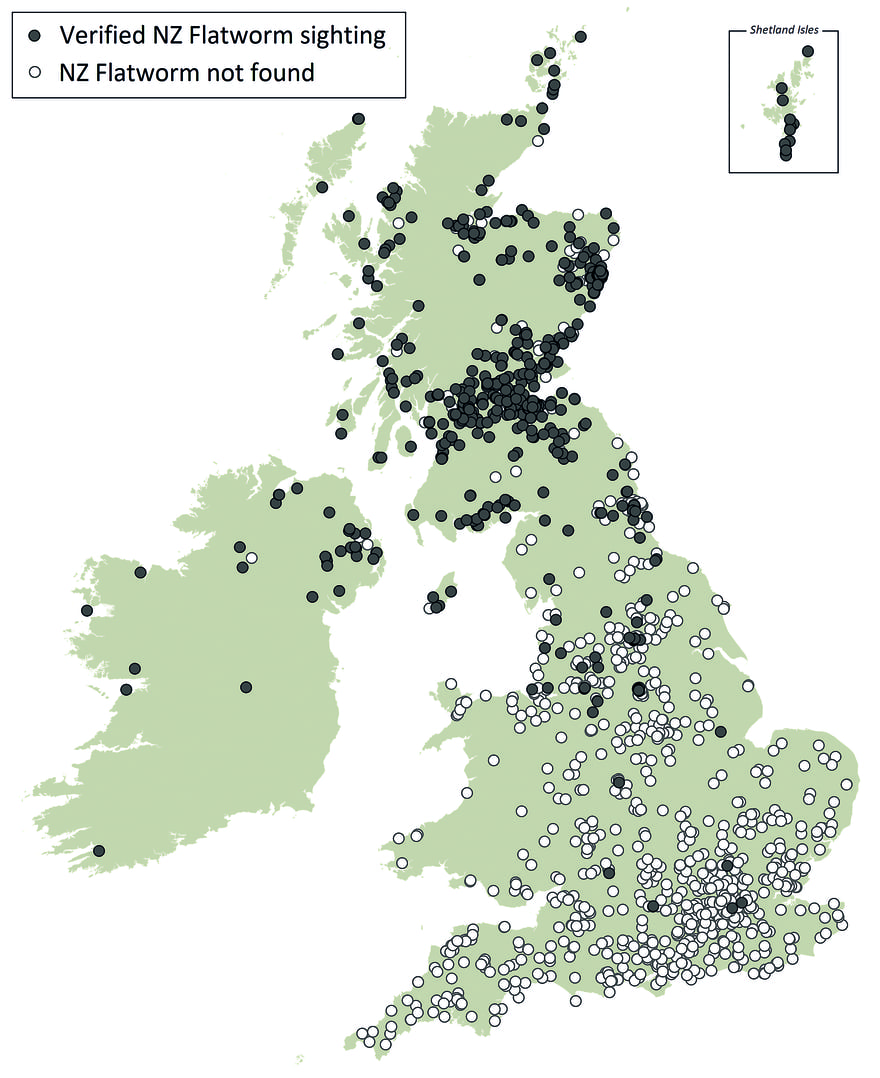

The New Zealand flatworm was inadvertently introduced to the UK in the 1960s, probably on plants sent to Scottish and Irish botanic gardens. By the 1970s it was being found in domestic gardens, and by the early 1990s there were repeated findings across Scotland, Northern Ireland and northern England. It is now widely distributed throughout Scotland, including all the major islands, and well established in Northern Ireland and northern England. It has also been found in central and southern England, Wales and the Republic of Ireland.

Research to date has been limited, but scientists in Aberdeen are now working to remedy that. The OPAL New Zealand Flatworm Survey, a citizen science initiative by Open Air Laboratories, the University of Aberdeen and the James Hutton Institute, began in 2015. Dr Annie Robinson of the University of Aberdeen says that as expected, most sightings are from the northern half of the country – but that records are now starting to come in from the Manchester and Sheffield areas, especially from allotments, and from around Birmingham, Luton and Swindon.

The flatworm Arthurdendyus triangulatus is native to New Zealand’s South Island, where it is found in cooler, wetter areas, and this correlates with the regions where it is most abundant in the UK. “New Zealand flatworms really do like cool and damp conditions,” says Dr Robinson. “They are really sensitive to desiccation; if you remove the wood or plastic or whatever they are under, they curl up to reduce drying out. New Zealand flatworms can be found in drier regions, but may be restricted to particularly favourable sites such as garden centres, nurseries and gardens that are watered regularly.”

The flatworm cannot tolerate direct temperatures below 0C or above around 20C, but with protection can survive hard frosts and summer heat. This is another reason why gardens, which offer refuges like pieces of wood and polythene, are a favourable habitat. “It is probably very protected from temperature extremes under carpet, which it loves,” says Dr Robinson. The flatworm cannot burrow, but it makes use of earthworm tunnels, she says, and may also retreat into those to avoid freezing or overheating.

Predators and prey

The New Zealand flatworm feeds by wrapping its body around an earthworm and secreting digestive enzymes which dissolve it, so it can then suck up the resulting earthworm soup. If the supply runs short, it can survive without food for over a year by ‘degrowing’, shrinking to as little as 10% of its body mass until it finds another earthworm. If the flatworm didn’t exist, science fiction would surely have invented it.

All our native earthworms are eaten by the flatworm, but the ones most at risk are the large ‘anecic’ species such as Lumbricus terrestris, which feed on the surface at night. Anecic species make permanent vertical burrows, so are especially important in ensuring good drainage. A long-term experiment in Ireland found a 75% reduction in L. terrestris numbers in land where flatworms are present.

Earthworms play a key role in creating and maintaining good soil. Their tunnelling activities aerate the soil, reduce compaction and improve drainage. They pull organic material down from the soil surface, and help to break it down. Fewer earthworms in a soil will impair its fertility and structure, and there is also likely to be a knock-on effect on wildlife which relies on earthworms as a major food source, including hedgehogs, badgers, moles, shrews and many species of bird.

Ironically, it seems that the UK’s abundant earthworm population is part of the problem; in New Zealand, there are fewer earthworms, and therefore fewer flatworms. “A relatively stable predator/prey equilibrium appears to exist there,” says Dr Robinson. Here, the earthworm bonanza means that its population is booming.

Little is known about flatworm predators in New Zealand, but there are few potential predators here. Wild birds do not seem to eat them – though chickens do – and there is no evidence of mammals or amphibians eating them, probably because they are unpalatably sticky. However, large predatory beetles like rove and ground beetles do eat them; these would need to be present in very high numbers to provide an effective biological control, but should definitely be encouraged.

Flatworm survey

The first step – if you don’t already know all too well – is to find out if you have flatworms in your garden, and while you’re doing that, the Aberdeen team would like your help. The OPAL New Zealand Flatworm Survey needs more records to create a full picture of just how far the flatworm has now spread.

Search your garden for 10 minutes, focusing on dark, damp places like under stones, and report your findings – whether or not you find flatworms – at www.opalexplorenature.org/nzflatworm

Flatworm control

If you don’t have flatworms in your garden, it’s worth going to considerable trouble to keep it that way. Once they are present, it is virtually impossible to get rid of them. However, you can reduce their numbers, limit their impact and stop their spread.

Gardeners are on the front line here, as it is all too easy to ferry flatworms between gardens when we swap plants, or move soil, compost or manure. They are frequently found in pots and containers, between the rootball and the wall of the pot. They can also be transported stuck to the bottom of pots, compost sacks or garden ornaments – or even on our boots.

If you’re given plants on which flatworms might have hitched a ride, heat-treat them or remove the soil

Prevention

• If you are given plants by a gardener from an area where flatworms have been found, remove all of the soil and dispose of it in a sealed plastic bag. Alternatively, immerse the pot and rootball in warm water (over 30C/86F) for 40 minutes. This will kill any flatworms or eggs present.

• Nurseries and garden centres are required to follow the DEFRA Code of Practice to Prevent the Spread of Non-Indigenous Flatworms, so plants bought from affected areas should be flatworm-free. If in doubt, heat-treat them or remove the soil.

• If you are importing any soil or home-made compost, make absolutely sure that it comes from a flatworm-free source, or has been heat-treated.

• Check under likely refuges – stones, pots and pieces of wood, plastic or carpet – regularly, and destroy any flatworms or egg capsules that you find.

• There are no chemical controls for New Zealand flatworms. Individual flatworms can be killed by dropping them into hot water or squashing them. Their mucus can be a skin irritant, so wear gloves if you need to handle them.

• Large predatory beetles and their larvae, especially rove and ground beetles, eat flatworms, so encourage their presence by providing beetle-friendly ground cover and avoiding pesticides.

• If you keep chickens, give them the run of your vegetable plots when you can.

• Do not move any soil, compost or manure out of your garden. If you want to give plants to other gardeners, remove all soil and re-pot them in bought compost, or give them bare-rooted plants, cuttings or seeds.

• Encourage your neighbours to employ these measures too, as flatworms are very mobile.

The flatworm research in Aberdeen is ongoing, and the university is now recruiting a graduate student to undertake a PhD entitled ‘Living with the enemy: how to minimise the negative effects of the invasive New Zealand flatworm on small-scale food production’, so more advice will be available to gardeners in years to come. The title, sadly, says it all: the flatworm is in the UK to stay, and the challenge is to find ways of minimising its impact. If your garden is still flatworm-free, however, you have the chance to keep it that way.

• Find out more at www.opalexplorenature.org/nzflatworm

Worms you do want

Unfortunately, tipping the balance in favour of earthworms is not a way of combating flatworms; increasing earthworm numbers simply boosts the flatworm population. But if you don’t have flatworms, encouraging more earthworms will improve your soil – and your crops.

• Add organic matter to your soil. Earthworms need food, and are scarce in impoverished soil, so enrich it with compost or manure and by growing green manures.

• Mulch as much as possible. Sheet mulching, where a layer of organic material is overlaid with cardboard, will create ideal habitat for earthworms while clearing overgrown ground.

• Dig as little as possible; some earthworm species make permanent burrows, and need undisturbed soil to thrive. However, if your soil is severely compacted, you will first need to break it up to give worms a chance to establish.

• Raise your soil pH by adding lime if necessary, as earthworms are scarce in acidic soil.

• Earthworms cannot survive in very dry soil, so keep it moist by using mulches and green manures, or by watering if necessary.

• Making compost or leaf-mould on the open ground, in open-bottomed bins or heaps, will encourage earthworms, which will move into the base of a cooling heap and help to break it down. (Worms found further up a compost heap, or in a plastic bin or wormery, will be specialised composting species; these are smaller than soil-dwelling earthworms and usually redder, with distinct rings.)

NZ flatworm Identification

• Dark purplish-brown upper surface with a narrow, beige spotted edge and beige underside.

• Ribbon-flat and pointed at both ends, with a completely smooth body surface.

• Size varies. A mature flatworm at rest is about 6cm (2½in) long and 1cm (½in) wide, but when extended can be up to 20cm (8in) long.

• Covered in sticky mucus, trails of which are left behind it.

• Found on the soil surface, and mostly active at night. During the day it shelters under refuges like stones or pieces of wood or plastic. When resting, it is curled up like a Swiss roll.

• Egg capsules resemble small, shiny, slightly flattened blackcurrants. They are laid in the soil or under shelters like stones.

• Each egg contains five to eight young flatworms, which are creamy-white or pink.

Other flatworms

There are many sorts of flatworms, living in a variety of habitats throughout the world. All are predatory – some, though unfortunately not the New Zealand variety, eat slugs. Native UK species of flatworm are small and inconspicuous; they pose no threat to earthworms and should be left alone.

Around 10 non-native species of flatworm are present in the UK, but the only other one of significance to gardeners is the Australian flatworm Australoplana sanguinea, which is 2 to 8cm (¾ to 3in) long and pinkish-orange. First recorded in south-west England in the 1960s, it has spread through southern and western England and Wales. However, although it also feeds on earthworms, it does not seem to be having such an impact.

Enjoy more Kitchen Garden reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more Kitchen Garden reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Sign-up to the Kitchen Garden Magazine Newsletter

Enter your e-mail address below to see a free digital back issue of Kitchen Garden Magazine and get regular updates straight to your inbox…

You can unsubscribe at any time.

About the Author

- The Cottage Garden Society ‘Grow In Pots’ For The Malvern Show 9-12 May - 12th April 2024

- Arundel Castle’s Tulip Festival returns - 7th February 2024

- FREE TREES FOR SCHOOLS - 4th January 2024